-

Nineteen Notes

for Elena del Rivero’s Nineteen Flags

by John A. Tyson

-

For me, the handkerchiefs hanging on the wall occupy the space between “torch” and “torchon.” —Walter Benjamin1

Género is the word in Spanish for “genre”; it is also the word for “gender.”

1. Walter Benjamin, On Hashish, trans. Howard Eiland, Michael Jennings, et. al. (Cambridge and London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006), 85.

-

“Thread, stretcher, loom, needle, and awl have their correspondence in writing: discourse, page, study, pencil, or quill.”2

2. José María Parreño, Elena del Rivero (Madrid: La Conservera, 2010), 37.

-

Typically, deftness with a pen or pencil is referred to as draftsmanship (or penmanship for handwriting); del Rivero always insists she is a “draftswoman.”

-

The grid, an ur-modernist form, is also found on kitchen rags.

-

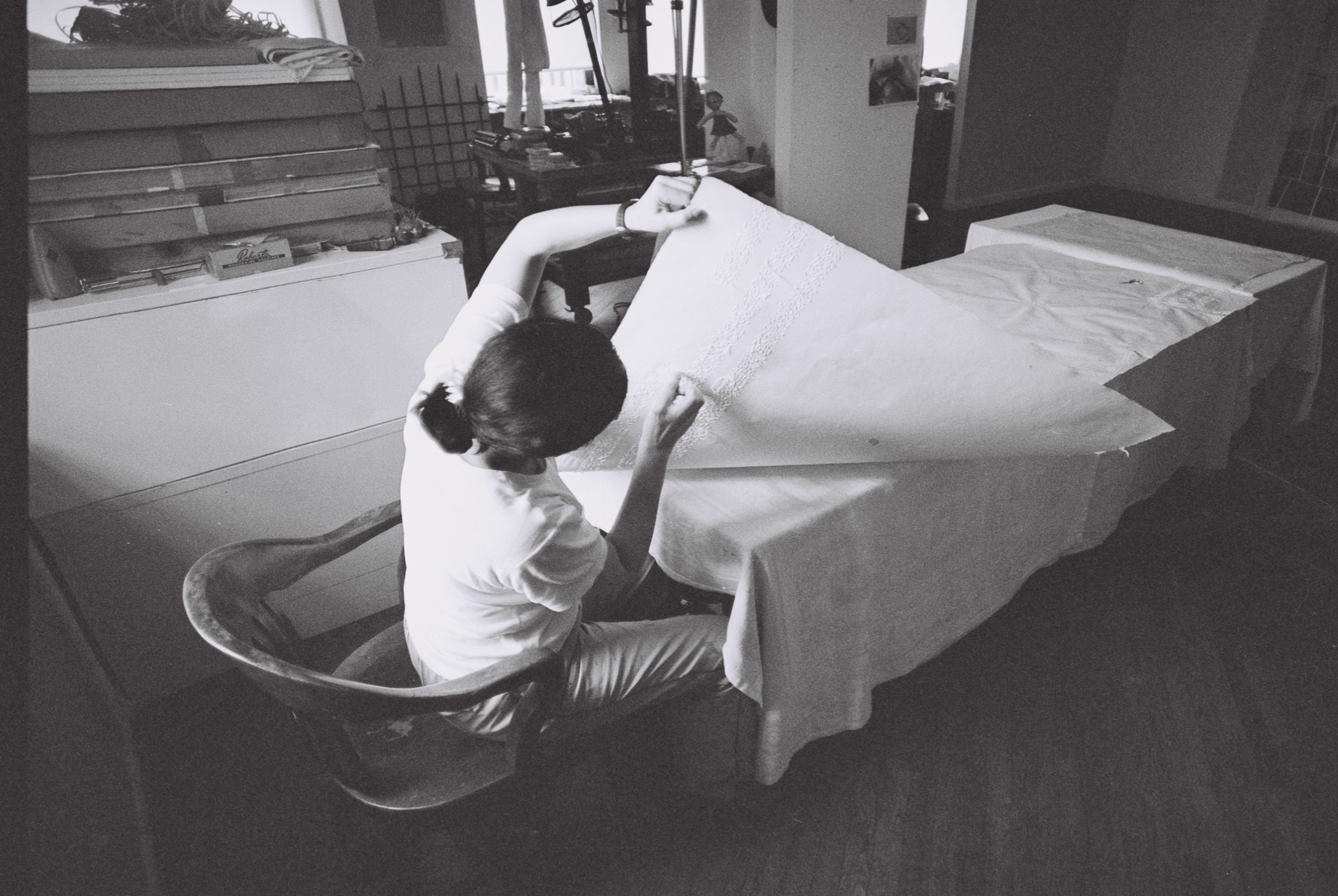

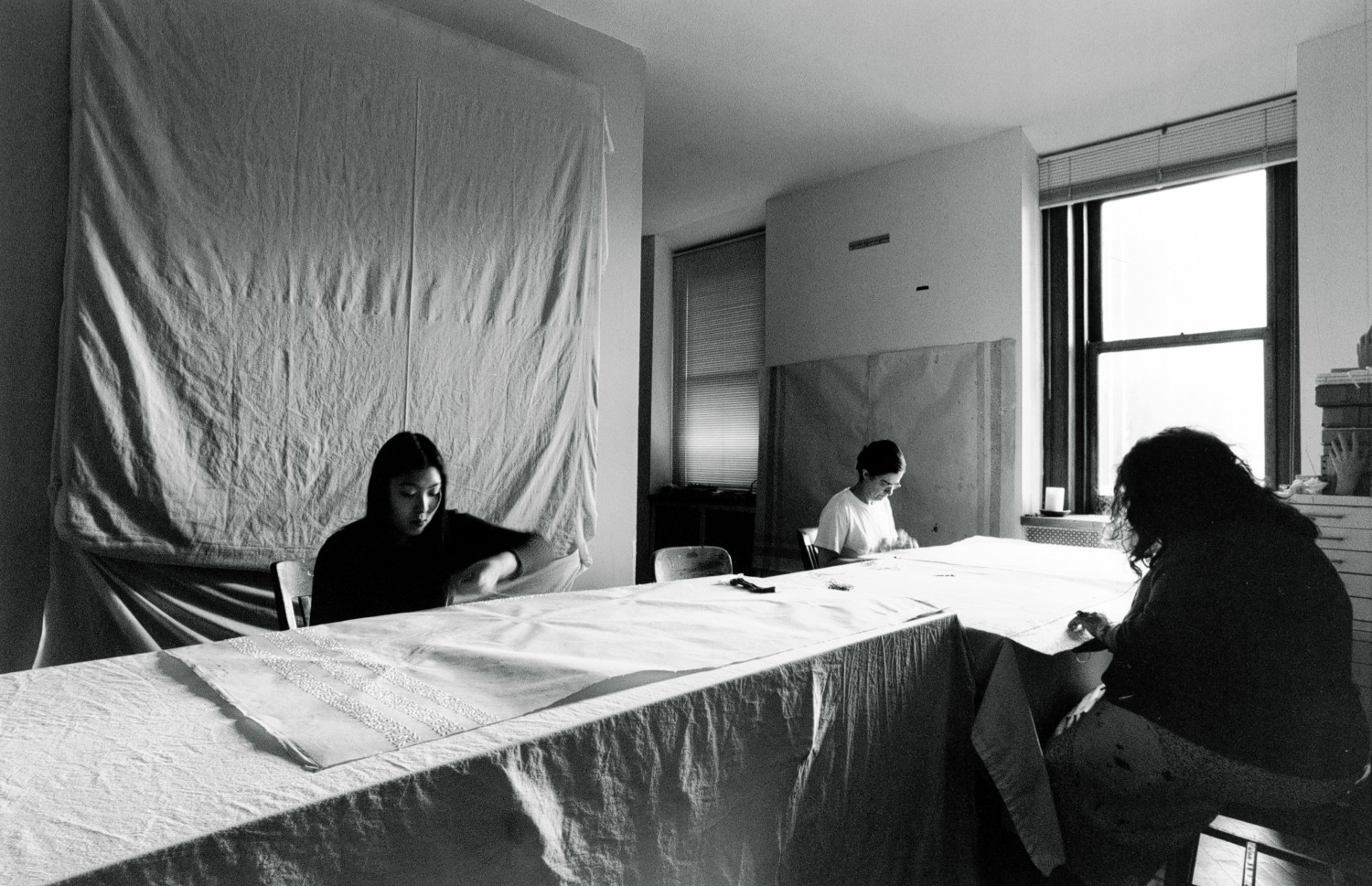

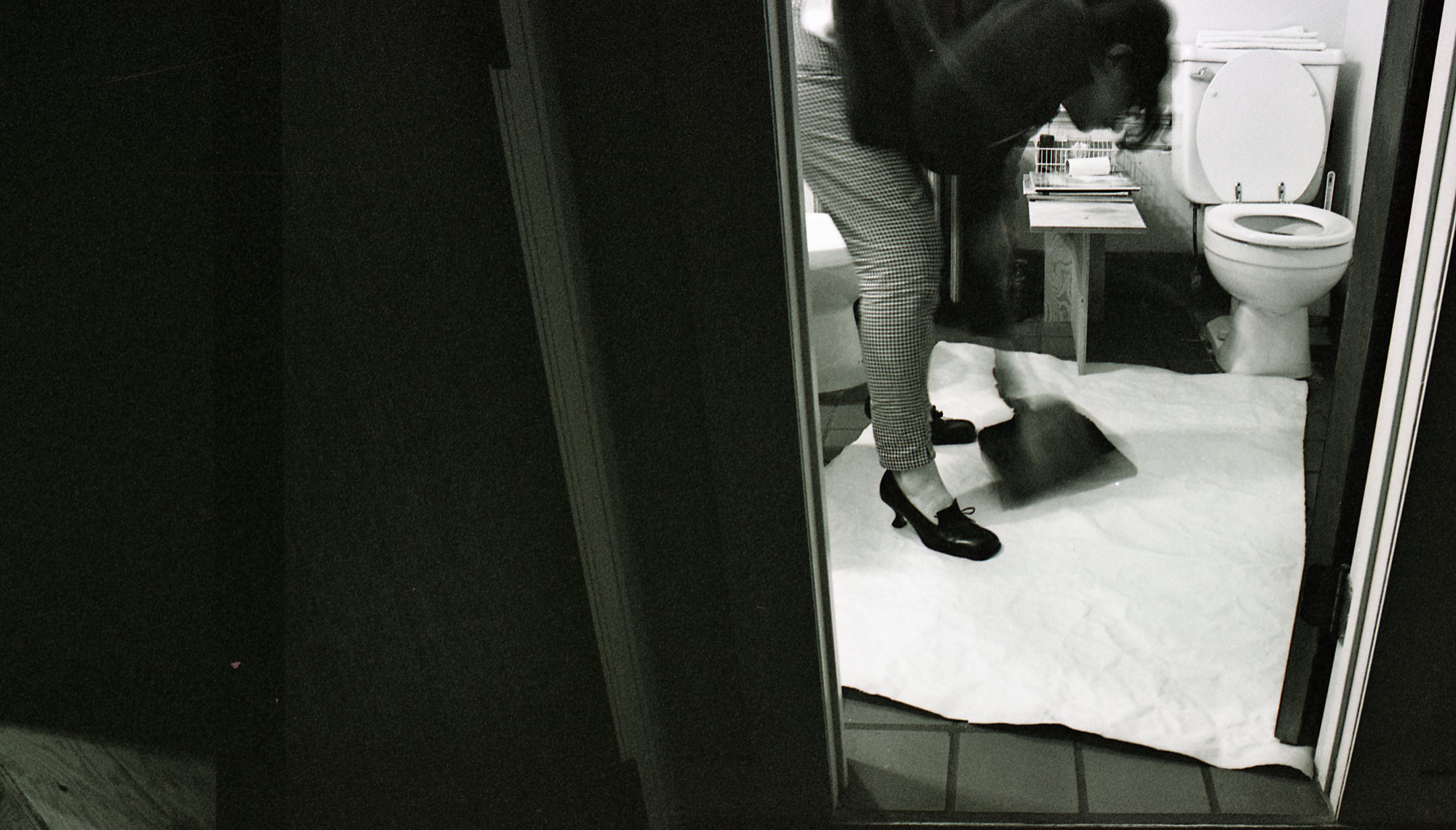

Del Rivero’s [Swi:t] Home (2001), the artist’s first engagement with the dishtowel form, involved a yearlong creation process. Del Rivero’s Cedar Street studio and residence in New York formed the project’s matrix and crucible. For six months, between 2000 and early 2001, twenty sheets of hand-made abaca paper (each 58 × 38 in.) covered the apartment’s floors, including the landing connecting her home to the stairwell. These sheets, taken together, approached a fragmented 1:1 scale map that began to merge with the real estate it occupied. The paper laid on the floor wore away as a result of human traffic, the movements of residents and visitors; it absorbed all kinds of domestic messes and materials by the end of its half-life with del Rivero.

-

When the sheets were returned to Dieu Donné Papermill in Brooklyn, papermakers repaired the tears with new pulp and the sheets were bathed, dried, and pressed again. The folios developed scarring, as the replacement areas woven into their fabric are a slightly darker beige tone.3 In the next six months del Rivero worked with assistants to transform the partially “healed” paper into a series of five massive dishtowels (each 115 × 78 in.). When they were later exhibited at the Drawing Center in New York, they were accompanied by an extensive reference library of artist’s books and documentation.4 Her textual repository included reflections upon and extensions of the ideas in codex form, including her own [Swi:t] Home Book of Hours, a technology that normally regulates prayer activities; a diary with 365 drawings; and documentation of the artwork’s creation.

3. Del Rivero selected the abaca paper because she believes its physical qualities are closest to skin. See Elena Del Rivero, “El más relacional hecho arte,” DUODA: Revista d’Estudis Feministes 23 (2002): 95.

4. Ibid., 92 (my translation).

-

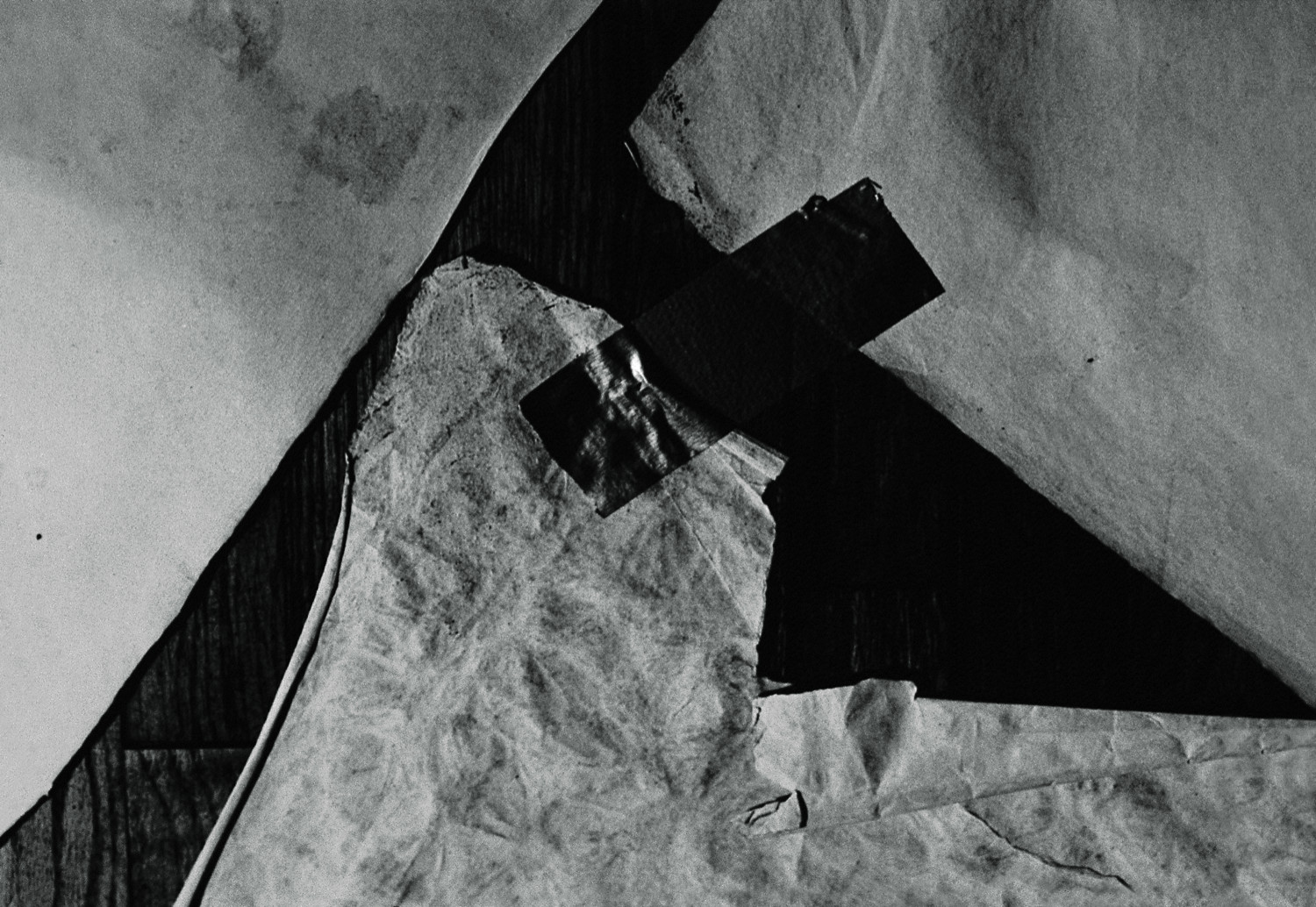

[Swi:t] Home might productively be viewed in relation to printmaking, of both the artistic and bureaucratic variety: spills, stains, tears, and repeated footprints impressed on the paper yield the marks.5 Domestic dirt impregnated the folios in much the way that ink enters fibers when sheets are run through a press. The impact of shoe soles created a kind of embossing. In the colossal dishtowels, there is also a tension between unruly accident and measurement. These marks represent, in some sense, a series of time stamps. In contrast to the more typical use of such a bureaucratic registration of a single moment, here strict schedules of labor (and surveillance) seem to be specifically resisted and rejected. Instead, a palimpsest of indexes of a long duration, as opposed to a single instant, pock their surfaces.6

5. Ed Ruscha’s Stains (1969), a series of prints-as-besmirchings made from mostly from foodstuffs readily encountered in an American home, seems like an important precedent.

6. The time stamp is a printed convention that migrated from workplace bureaucracies to video and photo technology.

-

[Swi:t] Home spanned distinct epistemes, taxonomies, social codes—the domestic and public, breaking and mending, housework and artwork. It signals the breakdown in professional and personal boundaries that can occur within the art world specifically and late capitalism more generally.

-

Del Rivero’s artworks rattle sabers with conventional accounts of modernism. Her series of monumental dishtowels emblazoned with geometric motifs and irregular splatters and smudges, “Letter from Home,” brings to the fore one of the repressed aspects of “high art”: paintings are really just stained swathes of fabric. Arguably, Clement Greenberg’s notion of “pictorial space,” the idea that a mark on a support yields an illusion of figure superimposed upon ground, is one final defense against seeing uncovered canvases for the materials they are made from.7 Del Rivero’s grids posit that dishtowel designs could possess this kind of illusionistic dimensionality when put in conversation with abstract canvases. In the context of del Rivero’s paintings, Greenberg’s affirmation, “thus a stretched or tacked-up canvas already exists as a picture—though not necessarily a successful one,” comes to define painting as the manipulation of cloth.8

7. See Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting,” in The Collected Essays and Criticism, Volume 4: Modernism with a Vengeance, 1957–1969, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 88.

8. Clement Greenberg, “After Abstract Expressionism” (1962), The Collected Essays and Criticism, Volume 4: Modernism with a Vengeance, 1957–1969, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 131.

-

Significant scholarly writing on the origins of tea towels and dishtowels is scarce. Systems of fabric production and economics often interweave, and the familiar gridded domestic textiles are the eventual result of international trade routes. The now ubiquitous European tea towels originated with the rise of the tea trade between China and European nations in the eighteenth century. With the rise of tea drinking, the accoutrements of the tea service became increasingly common household elements by the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Indeed, this was particularly true in the North American colonies. A visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s American Wing, which displays countless numbers of silver implements related to tea as well as porcelain services, reveals the significant expenditure on implements related to rituals of tea drinking in the early history of the United States. The tea towel was a particular type of woven linen employed by the lady of the house for drying her tea set, apparently a job that servants could not be trusted with.9 These textiles were often further decorated with embroidered designs. From at least the mid-nineteenth century, the type of checked and gridded tea towels that are familiar today have been mass produced and increasingly employed for drying all kinds of dishes.10 In the twentieth-century, dishtowels (with all kinds of patterns) became ubiquitous items in European and American households. They shifted from the purview of elites to become associated with a more bourgeois or even lower-class domestic sensibility: from the 1950s onward, tea towels increasingly were created for fundraising and sold as inexpensive tourist souvenirs.11

9. See Jessica Cumberbatch Anderson, “What the Heck are Tea Towels, Anyway?” Huffington Post: Home, November 12, 2014, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/11/12/what-are-tea-towels_n_6135252.html.

10. Ibid.

11. See Marnie Fogg, The Art of the Tea Towel (London: Pavilion Books, 2018) and Richard Till, Every Tea Towel Tells a Story (New Orleans: Renaissance Publishing, 2010).

-

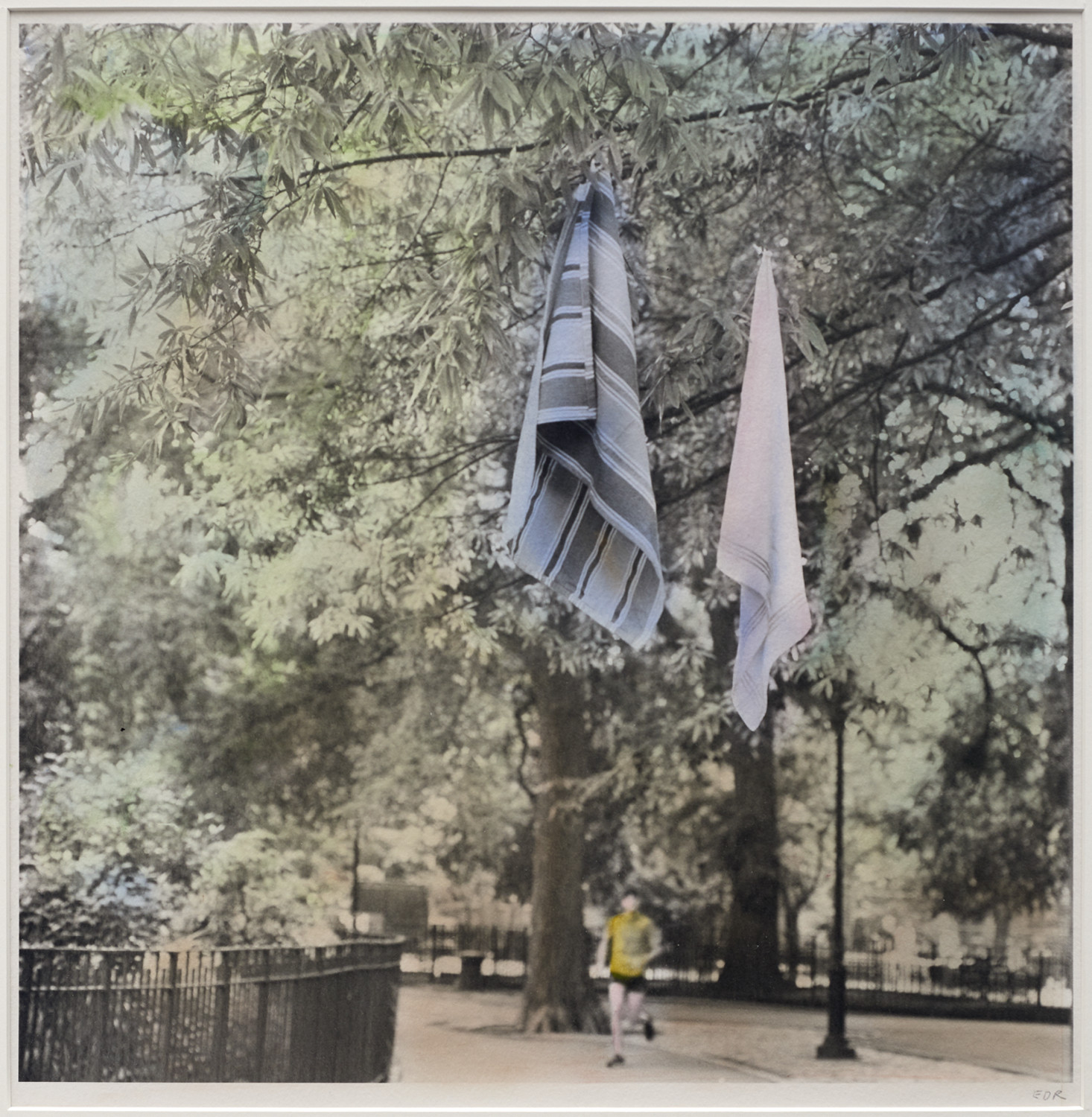

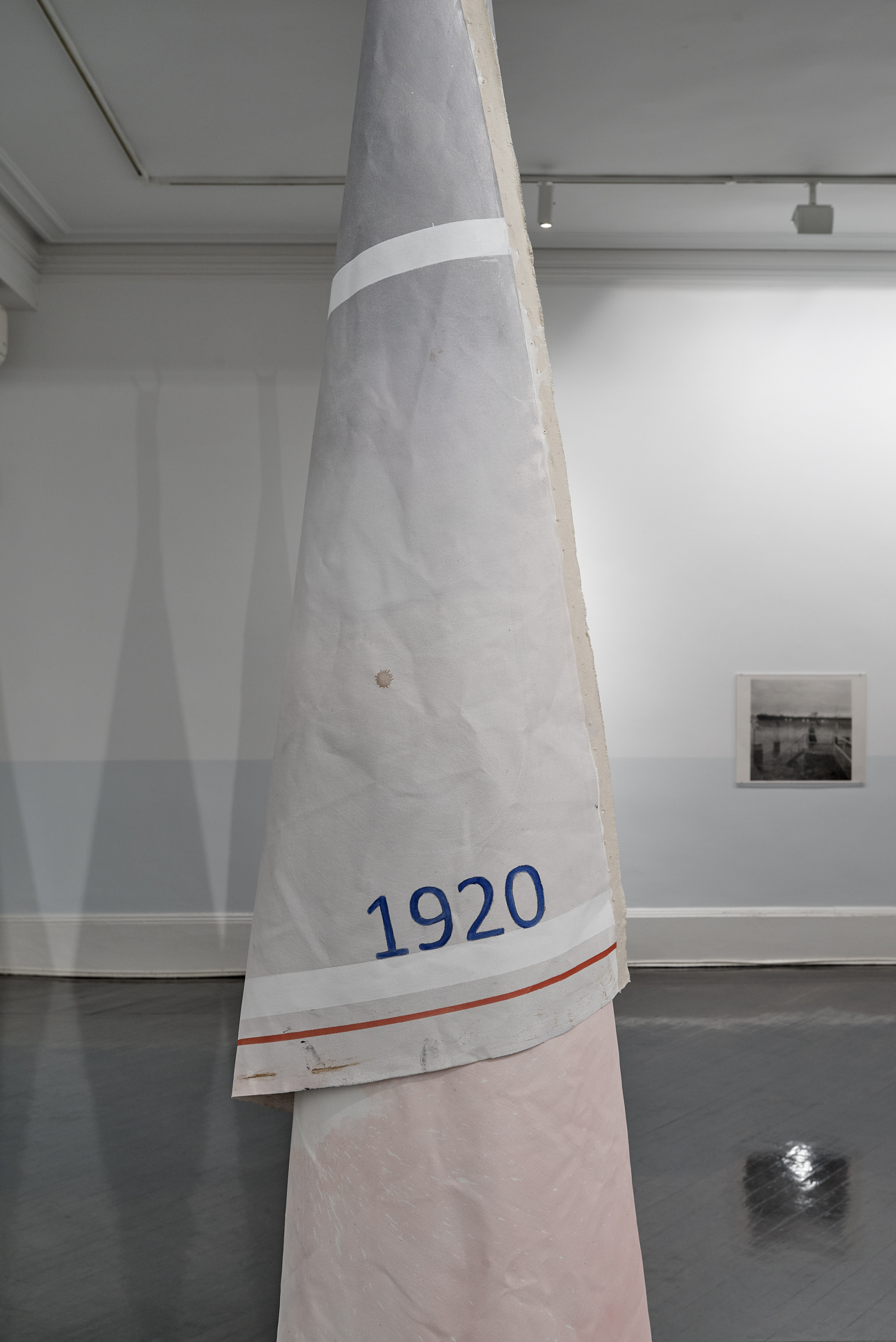

Epistolary exchange is central to Elena del Rivero’s oeuvre. Indeed, the name of her studio, the Paraclete, alludes to the medieval romance of Héloïse and Abelard, a nun and abbot who maintained an illicit relationship and rich correspondence. She decorates her “Letter from Home” canvases with crosses, stripes, and variations on grids. Letter from Home (for Marcel Duchamp) (2017) is a long, thin canvas with two sets of parallel red lines running up and down its edges. Letter from Home (for Marcel Broodthaers) (2017) recalls the cross of Saint George. Letter from Home (for Walter Benjamin) (2017) has a central trio of teal and red lines flanked by thin blue stripes on the edges. A series of thin, evenly spaced horizontal red lines, interspersed on either side by a pairing of lines—in thick ochre and thin blue—decorate Letter from Home (for Stéphane Mallarmé) (2017); it recalls a piece of writing paper or a garishly colored Agnes Martin. Del Rivero appended a stitched handle to all of these works, which enables them to hang from a peg in a domestic fashion. Rather than rest flush on a wall on taut stretchers, many of these works drape down in three-dimensional triangular bunches. Letter from Home (for Louis Kahn) is a double racing-stripe dishtowel that is scaled up to wall size; it competes with and covers architecture. In almost every case, del Rivero grinds in dirt and soaks in liquid, such that her canvases reveal use and hint at dwelling in quotidian spaces.

-

Beginning in 2016, del Rivero has dedicated each dishtowel painting to a male figure in the modernist canon, including Walter Benjamin, Aby Warburg, Louis Kahn, Stéphane Mallarmé, Marcel Broodthaers—and, of course, Marcel Duchamp.12 As Del Rivero explains, “I am not measuring myself against Duchamp; I am simply outlining a possible dialogue through difference, one that, I think, Luce Irigaray might approve of.”13

12. Her 2020 Letter from Home: Suffrage #6, to Mary Magdalene is the only exception I am aware of.

13. Del Rivero, “Artist Statement for [Swi:t] Home and Las Hilanderas (The Spinners),” cited in Thomas Girst, “Elena del Rivero and Marcel Duchamp: Les Amoureuses,” Tout-fait 2 (2002–2003), http://toutfait.com/elena-del-rivero-and-marcel-duchamp-les-amoureuses/.

-

On September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on New York City made the apartment that birthed [Swi:t] Home uninhabitable. Del Rivero was eventually allowed to return to recover the scraps of her artwork that had been exposed to the elements. As part of a process of working through the trauma losing her home and artwork, she produced [Swi:t] Home: A Chant (2001–2006), which del Rivero exhibited in 2019 at the Matadero in Madrid . In some sense, it is an uncanny double of [Swi:t] Home. The uncanny is that particular kind of familiar thing made strange and terrifying that preoccupied Sigmund Freud in his essay of the same name.14 In German, the term for uncanny (unheimlich) means unhomely—and Freud teases out the relevance of this linguistic connection to domestic spaces. Seemingly a giant dress train suspended from the ceiling and imposingly occupying space, [Swi:t] Home: A Chant contains shards of the artist’s domestic and business records and other assorted fragments hand-sewn to gauzy, white fabric. It is a literal marker of her un-homing. She followed this haunting material assemblage with another artwork, The Archive of Dust, a record of every fragment she collected after the devastation.15 While the name suggests Duchamp (Man Ray’s photo of Duchamp’s Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, Dust Breeding [1920]), the inventory of life shifts the focus from traces of trauma toward the performed process of picking up the pieces.

14. See Sigmund Freud, “The ‘Uncanny’” (1919) in Sigmund Freud, The Uncanny, ed. Adam Phillips (London: Penguin Classics EBooks, 2003), unpaginated, https://books.google.es/books?id=8f3-uKZOHekC&pg=PT5&dq=Freud,+%E2%80%9CThe+%E2%80%98Uncanny%E2%80%99%E2%80%9D&hl=es&source=gbs_selected_pages&cad=2#v=onepage&q=Freud%2C%20%E2%80%9CThe%20%E2%80%98Uncanny%E2%80%99%E2%80%9D&f=false.

15. Del Rivero, “El más relacional hecho arte,” 93.

-

Del Rivero’s most recent series, “Letters from Home: Suffrage” (2019–20), are various dishtowels that also involve spilling, staining, cleaning up, and mending. Given the temporal proximity of their creation to the centennial of the nineteenth amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave American women the right to vote, all the Letter from Home: Suffrage canvases register a specific history. Each towel is marked with a small, printed text reading SUFFRAGE. However, in the process of making the works around the anniversary, the artist became increasingly aware of the fact that, in practice, women’s suffrage often meant white, upper- and middle-class women’s suffrage; people of color continue to be excluded from American democracy. Del Rivero’s besmirching of all of the suffrage towels resonates with the fraught nature of commemorating a positive yet exclusionary event: by marring her flags, she reflects the fact that the centennial is sullied and must not be recollected as pure celebration.

-

Letter from Home: Suffrage #2, to Frederick Douglass incorporates wine, bleach, turmeric, and stitching. Douglass is best known for his anti-slavery activism. Nonetheless, he was also an important advocate for women’s rights: as he once said, “When I ran away from slavery, it was for myself; when I advocated emancipation, it was for my people; but when I stood up for the rights of women, self was out of the question, and I found a little nobility in the act.”16 The Black activist gets another afterlife when channeled into the context of del Rivero’s artwork. His commitment to women’s suffrage and ideas about (photographic) image making and the politics of representation rise out of the past.17 A prescient theorist of photography and one of the nineteenth century’s most often photographed individuals, Douglass should be recognized as a key figure of American modernism.

16. Frederick Douglass in David Cheesebrough, Frederick Douglass: Oratory from Slavery (Westport, CT and London: Greenwood Publishing, 1998), 36.

17. See Celeste-Marie Bernier, John Stauffer, Zoe Trodd, Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2015).

-

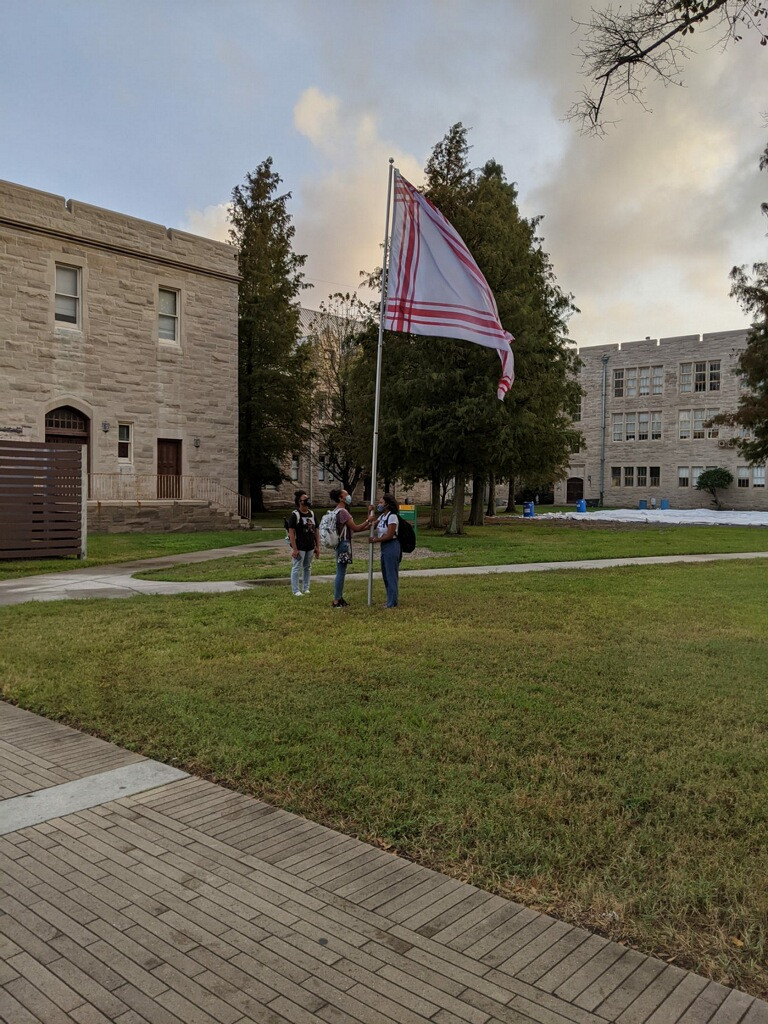

A multi-platform banner in an edition of nineteen, entitled Letter from Home (Suffrage), extends del Rivero’s critical commemoration project to even more public locations. The outdoor work combines a crisp, claret-red triple-rectangle grid that coexists with irregular burgundy stains on a white fabric ground. Del Rivero capitalizes on the fact that the geometric forms of the torchon-dishtowel are quite similar to the fields of flat color encountered in numerous national flags. This morphological link to established symbols of authority helps her banner achieve an uncanny quality; it short-circuits traditional expectations about textiles presented in public.

-

Of the numerous artistic forebears working with flags, it is David Hammons whose precedent she might aspire to follow most closely. Hammons’s African American Flag (1990), one of the five he editioned, has long hung from the facade of the Studio Museum in Harlem. The artwork renders the United States flag’s design in a palette inspired by The Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League’s Pan-African Flag; the white stars are black and the upper-left quadrant, normally blue, is green. Miniature versions are sold on the streets of Harlem, particularly coinciding with New York’s African American Day Parade. In early June 2020, Black Lives Matter demonstrators in Louisville, Kentucky flew the banner at protests in the wake of the murder of George Floyd.18

See Luke Sharrett’s documentation of Deandrea Barber with the African American flag illustrating “In Photos: Protesters March in Cities Across America,” New York Times, June 1, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/article/pictures-george-floyd-protests-photos.html.

-

In del Rivero’s projects, the flag evokes a longer history of feminist militancy. Banners paraded through the streets formed an essential part of the women’s suffrage movement.19 The color palette for her flags—burgundy and pink on white—evokes a variety of historical deployments of similar hues. White was the dominant color worn by suffragettes in the United States and United Kingdom. Del Rivero’s spare design also recalls the bold mauve stripes found on the VOTES FOR WOMEN sashes and buttons. The artist’s shifting of textiles from the domestic to the public sphere likewise resonates with more contemporary feminist activism. In 1962, Women Strike for Peace (WSP), an anti–nuclear arms movement, draped a massive dishtowel with signatures on the fence of the White House.20 The iconic pink knitted “pussy hats” of the January 2017 women’s marches used textiles and feminine-coded craft in order to protest the sexist regime of President Donald Trump. We should see del Rivero’s pink gridded flags as a corollary. They air the nation’s dirty laundry—an idea to which she has returned to in her recent flag work Ragline (2020).

19. For an account that sets these textiles into conversation with artworks, see Julia Bryan-Wilson, Fray: Art and Textile Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 9, 31.

20. Amy Swerdlow, “Female culture, pacificism, and feminism: Women Strike for Peace,” Current Issues in Women’s History, eds. Arina Angerman, Geerte Binnema, Annemieke Keunen, Vefie Poels, and Jacqueline Zirkzee (New York: Routledge, 1989), 120.

-

Jackson Pollock’s drips were charged with innuendo by some critics, who saw them as indexes of both sexual and artistic potency.21 Just as Pollock insisted that he brought intentionality and conviction to his mark making, del Rivero does wish her staining of Letter from Home (Suffrage) to be the “index of accidents.”22 Despite appearing to be the result of splashed and dripped red liquid, they are applied repeatedly and quite precisely via silkscreen. While they read as actual blemishes, the deliberate spills are best viewed as signs of stains. Hence, the banners revise the traditional associations with impurity and the repression of such cyclical excretions; they recode the ferrous red “soilings,” making them part of a celebratory emblem of feminine potency.23 The dishtowel-flags provoke an interrogation of the state of the nation and signal the continued need for equitable representation in government, as well as society’s continued ambivalence about female agency. 24 They ultimately underscore that politics is very much women’s work.

21. See Anna Chave, “Pollock and Krasner: Script and Postscript,” RES 24 (Autumn 1993), 98–100.

22. Ibid., 102.

23. For more on the connection between (Benjaminian) allegory and emblems, see Craig Owens, “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism,” October 12 (Spring 1980): 67–86.

24. I refer to the summer 2020 debates over Democratic vice-presidential candidates and the tendency to attack or criticize women with labels that would never be used for men. See Annie Linskey and Isaac Stanley-Becker, “Biden campaign, women’s groups are working to blunt sexist attacks on his vice presidential pick,” Washington Post, August 9, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/sexism-biden-vice-president-pick/2020/08/08/ad666a12-d5f3-11ea-aff6-220dd3a14741_story.html.

-

A Note on the Notes

Thanks to the generous editing of Andrea Andersson and this project’s feminist sprit of collaboration, these nineteen strands of text were picked out of a fairly traditional art-historical essay to become a suite of notes. The form owes debts to the strategies of key figures for del Rivero’s work as well as my own thinking about art history. Her output seems to weave through Marcel Duchamp’s The Green Box, which has ninety-four elements; Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project, with its thirty-six sections of fragments; and the notational writings of Rosalind Krauss, especially on the subject of the grid. So, too, can it reference the curatorial form of Lucy Lippard’s “Numbers” shows.

Beyond the forced domesticity of COVID-19, the fallout from the virus has produced a series of funding and access issues for the world of art. Thus, I am thankful that del Rivero’s missive/missiles, to draw upon Jacques Derrida’s punning insights, have been sent out to real flagpoles. Were it not for our peculiar situation, I’m not sure I would have fully registered the virulent backdrop around the struggle for women’s suffrage some one hundred years ago. Let us recall that the victory of the Nineteenth Amendment came despite the Spanish Flu: similarly, we are not just in the throes of COVID-19, but also in the era of Black Lives Matter, Decolonization, and #MeToo. We can only hope that the triumphs and legacies of these social movements eclipse (without effacing) histories of sickness and death at the second centennial anniversary.